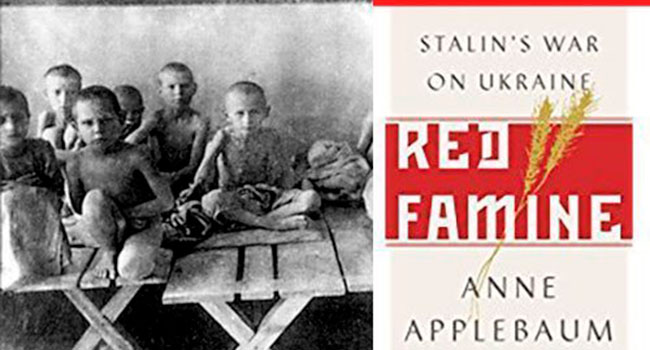

Chances are Anne Applebaum’s Red Famine will set the cat among the pigeons with respect to the horrendous Ukrainian hunger of 1932-33. It’s already touched off a rhetorical skirmish between the author and an early reviewer.

Chances are Anne Applebaum’s Red Famine will set the cat among the pigeons with respect to the horrendous Ukrainian hunger of 1932-33. It’s already touched off a rhetorical skirmish between the author and an early reviewer.

Applebaum is an American journalist-historian whose Gulag: A History won a 2004 Pulitzer Prize. Russia is a particular specialty of hers and, to put it mildly, she’s a persistent critic of President Vladimir Putin.

Most of the facts about the famine – the Holodomor in Ukrainian – are generally acknowledged.

First, it’s agreed that it actually happened. Although the famine’s existence was initially denied by both the Soviets and their western fans – particularly Walter Duranty of the New York Times – nobody seriously disputes it anymore.

Second, there’s wide agreement that the death toll ran into the millions. Applebaum puts the number in the vicinity of four million and other estimates go higher.

And third, there’s agreement that Soviet government actions heavily contributed to the debacle. The argument revolves around whether it was a deliberate killing policy.

To begin with, there was Soviet dictator Josef Stalin’s forced collectivization of agriculture. In an ideological milieu enamoured with the wisdom of top-down planning, this was intended to generate efficiency gains. However, many peasants bitterly resented the loss of independence and resisted where they could.

Then there was the seizure of grain. Along with collectivizing agriculture, Stalin’s crash modernization program called for expedited industrialization, which was to be partly financed through grain exports. Convinced that the peasants were withholding grain, Stalin’s agents took everything they could find that was edible, including the seed for the next year’s crops.

And there was the decision to seal Ukraine off so nobody could leave. At the same time, peasants were prevented from migrating to the cities.

As one can imagine, the resulting situation was horrific. In Applebaum’s telling, there were even outbreaks of cannibalism where, for instance, parents “killed their children and used their flesh for food.”

Historians are divided on the matter of Stalin’s intent.

There are those who tend to put most of the blame on administrative mismanagement, incompetence, paranoia and misplaced ideological zeal. Millions may have died but that was an unfortunate byproduct rather than the primary goal.

Stalin, in this rendering, believed that his modernization efforts were being sabotaged by “class enemies.” And his chief villains were the kulaks, loosely defined as the most prosperous peasants. If the kulaks were going to resist, their hoarding sabotage wouldn’t be tolerated. He’d squeeze the grain out of them.

Other historians are more skeptical.

For instance, Timothy Snyder notes that as early as 1930, Stalin had declared his intention to “liquidate” the kulaks as a class. And while acknowledging that Stalin’s motivations “remain frustratingly elusive,” Norman Naimark looks at the totality of his policies and concludes that he viewed Ukrainian peasants as an “enemy nation” in need of brutal transformation.

This question of intent sparked the aforementioned rhetorical skirmish between Applebaum and an early reviewer.

Writing in the Guardian on Aug. 25, Australian historian and Russian specialist Sheila Fitzpatrick observed that Applebaum “ultimately doesn’t buy the Ukrainian argument that Holodomor was an act of genocide.”

Two days later, Applebaum angrily fired back: “That is exactly the opposite of what I wrote – 180 degrees of difference … the central argument of my book, which she does not ever address in her review, is that Stalin intentionally used the famine not only to kill Ukrainians but to destroy the Ukrainian national movement, which he perceived as a threat to Soviet power, and to destroy the idea of Ukraine as an independent nation, forever.”

Part of what’s transpiring here is the refining of history as hitherto closed archives become available. It’s a process that’s naturally susceptible to differing definitions and interpretations.

Part is related to national myth-making. As nations emerge or re-emerge, there’s a tendency to position stories in a light that emphasizes suffering. A sense of having been a victim can be a powerful force for national binding.

And finally, there’s a residual sensitivity around what’s perceived as excessive criticism of the former Soviet Union. To a significant slice of the intelligentsia, it was a noble experiment that went inexplicably awry. Some broken hearts don’t mend.

Troy Media columnist Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well perhaps a little bit.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.