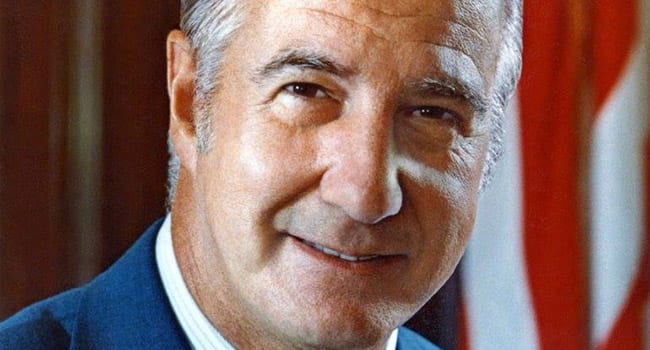

Spiro Agnew – the 39th vice-president of the United States – was born in 1918 to a Greek immigrant father and a native-born American mother. In keeping with the integrationist pattern of the era, his father changed the Anagnostopoulos surname to Agnew. It was important to fit in and get along.

Spiro Agnew – the 39th vice-president of the United States – was born in 1918 to a Greek immigrant father and a native-born American mother. In keeping with the integrationist pattern of the era, his father changed the Anagnostopoulos surname to Agnew. It was important to fit in and get along.

Agnew’s early life was ordinary. He was drafted in 1941, served in Europe and fought at the pivotal Battle of the Bulge. Post-war, he went to night school and got a law degree.

After cutting his teeth in local Maryland politics, Agnew moved up the ladder as the 1966 Republican gubernatorial candidate. And running against a segregationist Democrat in a heavily Democratic state, he won decisively.

Agnew’s Maryland profile was that of a pragmatic moderate. He was considered progressive on civil rights, working to eliminate the historical state ban on biracial marriage and to end discriminatory housing practices. In national presidential politics, his tendency was to gravitate towards liberal Republicans.

But the social upheavals and rising crime rates of the period brought out another aspect of Agnew’s political personality. Unlike some, he didn’t subscribe to the idea that the imperative in dealing with rioting and violence was to “understand the root causes.” His reflexive response was hard-nosed and pugnaciously unsympathetic.

The flashpoint came in April 1968, via the violent Baltimore rioting that followed Martin Luther King’s murder. Agnew publicly took the local civil rights leadership to task for what he saw as their inappropriate response. In the process, a hitherto amicable working relationship was sundered.

Agnew was relatively unknown nationally when he was tapped as a compromise vice-presidential choice on Richard Nixon’s 1968 ticket. And media coverage of the campaign wasn’t complimentary towards him, particularly in contrast to the “Lincolnesque” portrayal of his Democratic counterpart Edmund Muskie.

Meanwhile, the wily Lyndon Johnson had a different take, crediting Agnew with helping to win several states for Nixon. Caustically shrewd, Johnson thought “the press had slobbered over Muskie,” who had only delivered the four electoral votes of his native Maine.

In 1969, Nixon’s first year in office, Agnew became a major political figure in his own right. He did it by taking on the press.

Back then, the American media was considerably less fragmented than today. National TV news essentially came from three networks – CBS, NBC and ABC. And two major liberal newspapers – the New York Times and the Washington Post – played an outsize role in deciding what news topics the networks would cover, how they’d frame the stories and what narratives they’d pursue.

Ostensibly, the media consisted of tough-minded, skeptical journalists dedicated to giving you the whole story. In reality, there was a substantial element of group think. And that disposition was generally liberal and unsympathetic towards the Nixon administration.

Agnew went after this tendency in a series of controversial speeches, most notably in Des Moines, Iowa, on Nov. 13, 1969. The speech created a furor.

Various media luminaries accused Agnew of trying to silence critics by impugning their patriotism. Still, lots of people agreed with him, believing he was only saying in public what many thought in private but didn’t dare say aloud. One Republican politician even saw it as a self-destructive act: “No one with national political ambitions would tackle the networks.”

However, what ultimately brought Agnew down was his own corruption. In the grand tradition of Maryland politics, he’d been on the take.

Agnew didn’t invent the practice of accepting kickbacks on public contracts. Privately, he averred that “everyone else in Maryland politics did it, so why shouldn’t I?”

But when prosecutors closed in on him in 1973, he agreed to a deal. In return for resigning the vice-presidency and pleading no contest to tax evasion, the government agreed to forego other charges. There was also a three-year suspended sentence and a $10,000 fine.

Agnew never forgave Nixon for what he saw as abandonment in his hour of need. Years later, he refused to take Nixon’s calls and avoided events where they might come in contact. It was only after a personal request from Nixon’s daughter Tricia that he agreed to attend Nixon’s 1994 funeral.

When, two years later, he died suddenly from undiagnosed acute leukaemia, Agnew was a more or less forgotten figure. Once upon a time, he’d been among the most admired men in America.

Troy Media columnist Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well perhaps a little bit.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.