The 2020 Summer Olympics in Tokyo, Japan, are over. They came pretty close to never materializing, however.

The 2020 Summer Olympics in Tokyo, Japan, are over. They came pretty close to never materializing, however.

The Tokyo Games were delayed a year due to the coronavirus pandemic. And a surge in COVID-19 cases in Japan this year led some health experts to suggest the Olympics should be cancelled.

The Japanese newspaper Asahi Shimbun reported in late July that 55 per cent of Japanese survey respondents didn’t want the Games to go ahead. Some athletes opted to stay home due to these warnings.

Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga, much like his successor Shinzo Abe, was determined to hold the Olympics. He declared a state of emergency in Japan. Friends and families wouldn’t be allowed to join the athletes. The Games would be held behind closed doors with no spectators.

This would lead to a huge financial loss. The year-long postponement had already reportedly cost Japan about US$2.8 billion. The loss of an additional several billion dollars will occur this year due to the elimination of travel and tourism.

Then again, Japanese broadcaster NHK reported on March 30, 2020, that a complete cancellation could have cost in excess of US$41.5 billion. Little wonder Suga was determined to hold the Summer Olympics by hook or by crook.

To Japan’s credit, everything worked out.

To Japan’s credit, everything worked out.

The Tokyo Olympics were held from July 23 to Aug. 8. The number of COVID-19 cases among athletes was minimal. The events conducted under unusual conditions only experienced a few hiccups. The hope of having a short-term distraction to the pandemic was achieved.

The United States finished first with 113 medals, including 39 gold. China, which had led most of the way, finished second with 88 medals and 38 gold. Japan ended up third with 58 medals and 27 gold.

Canada had its best-ever showing at a non-boycotted Summer Games. Our country finished in 11th place with 24 medals (seven gold, six silver and 11 bronze). The highest previous tally was 22, achieved at Atlanta 1996 and Rio de Janeiro 2016. Female athletes took the lion’s share of medals, in 18 events.

There were many highlights:

- Canada won its first gold medal in women’s football.

- The nation also won its first bronze in women’s softball.

- Swimmer Penny Oleksiak became this country’s most decorated Olympian with seven medals, including a silver and two bronze in Tokyo.

- Track and field star Andre De Grasse won his first gold medal in the men’s 200 metres and two bronze medals (100 metres and four-by-100 relay).

- Damian Warner became the first Canadian to win a gold medal in men’s decathlon and set an Olympic record with 9,018 points.

- Kelsey Mitchell won the country’s last medal in Japan with a gold in women’s track cycling sprint.

Canada’s seven gold medals tied the record tally achieved in Barcelona 1992 for a non-boycotted Summer Olympics. That’s nearly one-10th of all the gold medals Canada has ever won (71) in the warm-weather games.

This made me recall Mark Hebscher’s 2019 book The Greatest Athlete (you’ve never heard of): Canada’s First Olympic Gold Medallist.

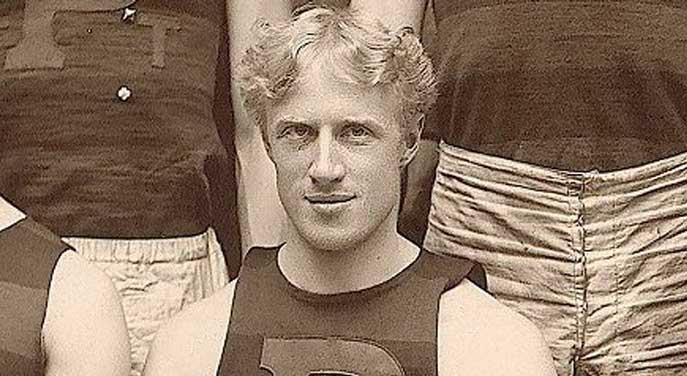

Hebscher, a longtime sports broadcaster, knew almost nothing about the remarkable life and career of George Washington Orton. The book’s main protagonist was “rendered disabled at age three” but went on to become a star athlete in hockey and track and field. He was “fluent in nine languages and armed with a PhD in philosophy.” He initiated the idea of “placing numbers” on football jerseys, “popularized the use of a stopwatch” for track athletes, and “introduced ice hockey to Philadelphia,” among other things.

Yet the man who was born in Strathroy, Ont., and won Canada’s first gold medal in the 2,500-metre steeplechase in the 1900 Summer Olympics in Paris was barely known in his own country. According to Hebscher, he wasn’t even elected to the Canadian Olympic Hall of Fame until 1996!

Why?

Orton’s success occurred during a time when medals weren’t handed out for every sport at a particular Olympics. Some would arrive years later and he could have received his medal as late as 1908.

Nationality was also of secondary importance to the International Olympic Committee. Orton was actually misidentified for seven decades due to his stature in the U.S. As Hebscher wrote, “prior to 1972, The Olympian Record Book listed Orton as an American.”

Canadians treat today’s Olympic athletes with the respect and honour they deserve. If we didn’t, the accomplishments achieved at the Tokyo Games would disappear with the sands of time much the way that national recognition for George Washington Orton, Canada’s first gold medallist, didn’t occur for several generations.

That’s almost unimaginable. Alas, Olympic glory hasn’t always been paved in gold in the Great White North.

Michael Taube, a Troy Media syndicated columnist and Washington Times contributor, was a speechwriter for former prime minister Stephen Harper. He holds a master’s degree in comparative politics from the London School of Economics. For interview requests, click here.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the authors’ alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.