January is book month in our house. It’s when we finally come to grips with reading all the titles that accumulated over Christmas and, in my case, a January birthday.

January is book month in our house. It’s when we finally come to grips with reading all the titles that accumulated over Christmas and, in my case, a January birthday.

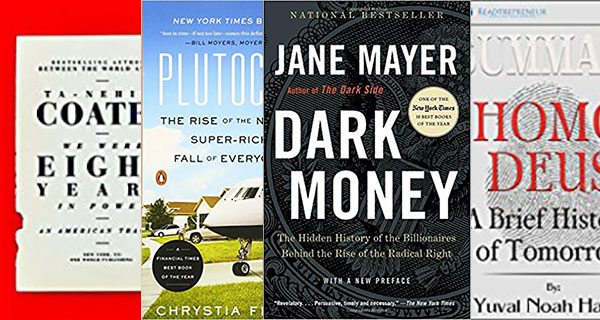

I’ve read Ta-Nehisi Coates’s We Were Eight Years in Power: An American Tragedy, Chrystia Freeland’s Plutocrats: The Rise of the Rise of the New Global Super-Rich and the Fall of Everyone Else, Yuval Noah Harari’s Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow, and Jane Mayer’s Dark Money: the Hidden History of the Billionaires Behind the Rise of the Radical Right.

These books are uniquely inter-related, beautifully researched, au courant and collectively depressing.

I say depressing because they register with me profoundly while I’m still developing survival mechanisms to cope with the Donald Trump presidency and its daily takedown of regulations, treaties, laws and public funding for the basic elements of what I consider civilized life.

For the past year, I’ve self-diagnosed an ongoing low-grade depression, which underpins my psyche. I know it’s there because things that ordinarily didn’t depress me – like reading insightful, future-oriented prose – now do. It’s as if a tipping point has been reached in my mind.

Coates chronicles the eight years of Barack Obama’s presidency with great passion and analysis. The main chapters are eight expanded essays that originally appeared in The Atlantic magazine. They describe how a man of African descent managed two terms as president of the United States with care, thought and distinction. It was possible to dream that America had made racial progress. It exemplified the power of decency and rational thought on topics ranging from stopping the collapse of the U.S. banking system, to negotiating the Paris Agreement on climate action, to the Iran nuclear deal framework to restrain nuclear proliferation.

And then it all came to an end in a vulgar electoral crash.

Harari’s book considers the history of man’s quest to become digital, algorithmic gods. Now that we’ve conquered famine, plague and war, we have a new human goal: to become godlike. He brilliantly summarizes our potential future into short, medium and long-term horizons. Today, we must deal with Kim Jong-un and Trump’s shortcomings; tomorrow, it’s vanquishing the perils of climate change. But ultimately, it’s coming to grips with digitization and the potential loss of human consciousness.

Harari leaves us with the feeling that it’s our lack of attention to the long-term implications of information technology that will ultimately do us in. He thinks we’re vulnerable to capture as a species by artificial intelligence, machine behaviour and a loss of the essence of human serendipity. We’re already in a world, he cautions, where 300 Facebook ‘likes’ reveal more algorithmically about an individual than the sum knowledge of long-term spouses or parents.

Freeland and Mayer add to our angst by detailing the lives of the .01 per cent — the mere thousands of humans whose net worth eclipses more than 50 per cent of humanity’s collective savings. The plutocrats are described by both authors as living in bubbles, completely divorced from everyday human reality. They form a transnational uber-class of private jet and high-tech yacht owners, who maintain multiple international residences and stress about extending their lifespans out as far as 200 years.

These contemporary information technology plutocrats are largely characterized by Freeland and Mayer as Davos-devotees, favouring international offshoring, free trade and a digitizing of humanity.

However, an old guard of largely oligarchic industrialists and oilmen are also profiled. Through family foundations set up to promote tax avoidance and right-wing politics, their founders and heirs have used think-tanks, economics and law faculties, alt- right media and, increasingly, even the courts to promote a minimalist role for government.

One of them, Charles Koch, is quoted by Mayer defining this role: to “serve as a night watchman, to protect individuals and property from outside threat, including fraud. That is the maximum.”

Taken as a whole, these four books portray a future that must trouble humanists, democrats, minorities, devotees of the arts and humanities and, in Harari’s words, “anyone with a conscience.” I would add: anyone with a basic sense of compassion.

Troy Media columnist Mike Robinson has been CEO of three Canadian NGOs: the Arctic Institute of North America, the Glenbow Museum and the Bill Reid Gallery.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.