The teenage Isabel de Clare was a desirable prize in the late 12th century marriage market. As the heiress to substantial lands in Ireland, Wales, England and Normandy, she had much to offer.

The teenage Isabel de Clare was a desirable prize in the late 12th century marriage market. As the heiress to substantial lands in Ireland, Wales, England and Normandy, she had much to offer.

Both sides of her pedigree contributed to this inheritance.

Isabel’s father was Richard de Clare, popularly known as Strongbow. He came from a Norman family that had arrived in England with William the Conqueror and his great-grandfather became a large post-conquest landholder.

Isabel’s mother was Aoife Mac Murchada, daughter of the 12th century Gaelic king Diarmait Mac Murchada. The Mac Murchadas were a long established Irish family with traditional territories in Ireland’s southeast.

However, having run into a spot of bother with respect to possession of his kingdom, Diarmait recruited Strongbow to help him take back what he saw as rightfully his. The bait was twofold: Strongbow would have Aoife’s hand in marriage and be designated as Diarmait’s heir.

As a business proposition, it was executed smoothly. Diarmait was quickly restored but died shortly thereafter and Strongbow succeeded him.

Just five years later, Strongbow himself died, leaving Aoife with two young children. There was a boy called Gilbert and a girl called Isabel.

In Anglo-Norman eyes, the marriage between Strongbow and Aoife had united the holdings of the two families, which were then subject to the usual Anglo-Norman inheritance protocols. There being no adult heir, the Crown assumed responsibility for the interim administration of the estates.

When Gilbert subsequently died before attaining adulthood, Isabel became the sole surviving claimant. And as a royal ward, it was the king’s prerogative to decide on the selection of her husband.

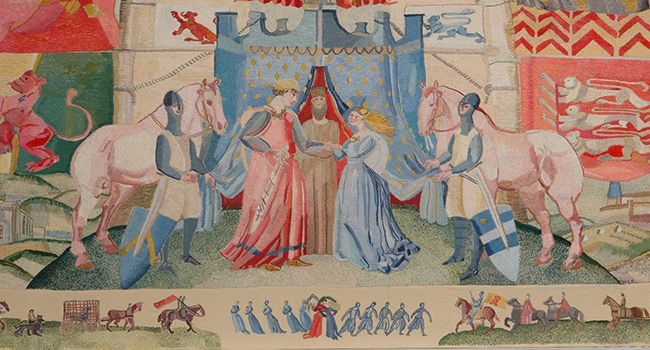

The prize winner, William Marshal, was an older man. At the time of their 1189 marriage, Isabel was 17 and he was 42 or 43.

Marshal’s family had also come to England from Normandy but weren’t nearly as grand as the de Clares. Besides, Marshal was a fourth son and thus had to work for a living. So he became a soldier, perhaps the most accomplished of the era.

The combination of Isabel’s inherited wealth and Marshal’s earned status made for a fortuitous pairing. They were the epitome of a medieval power couple.

Despite the age difference, the relationship seems to have been successful. They had 10 children, five boys and five girls. And unlike many such marriages – think Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine – there’s no hint of any estrangement between them.

Indeed, the evidence suggests that Isabel’s role was more extensive than just providing her inheritance. Like her mother before her, she became something of a player in her own right.

It was in Ireland that Isabel’s influence was most clearly felt. Given her antecedents, she was the key to legitimacy there. Historian David Crouch believes that “her advice and consent was both needed and sought.”

Marshal’s relations with the Crown had been positive during the reigns of Henry II and his immediate successor, Richard the Lionheart. But when Richard died unexpectedly and was replaced by his brother John, things got trickier.

Matters came to a head in 1207 with John actively seeking to undermine the family’s position in Ireland. For a while, the situation was dicey. However, thanks in part to Isabel’s political savvy and personal standing, the challenge was seen off.

As John’s benighted reign sputtered towards an end, even the reluctant – and insincere – concessions of Magna Carta couldn’t placate the unhappy barons, a group of whom turned to Louis, the son of the French king. In due course, Louis arrived in England with an army and a full-scale revolt ensued.

Marshal was one of the few Anglo-Norman magnates to actually stand with John in his hour of need but it was tough sledding. Then, in a stroke of good luck, John died, at which point his nine-year-old son was crowned Henry III and Marshal was appointed regent. Within a year, Louis was sent packing and Marshal was the de facto ruler of the Anglo-Norman world.

It didn’t last long, though.

By now in his 70s, Marshal died in 1219 and Isabel followed a year later.

And although all five sons grew into adulthood, none lived past 45 nor left legitimate issue. Consequently, the vast landholdings were partitioned between the families the daughters married into.

The aggregation of family power and influence created by Isabel’s inheritance and marriage thus vanished into the mist.

Troy Media columnist Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well, perhaps a little bit.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.