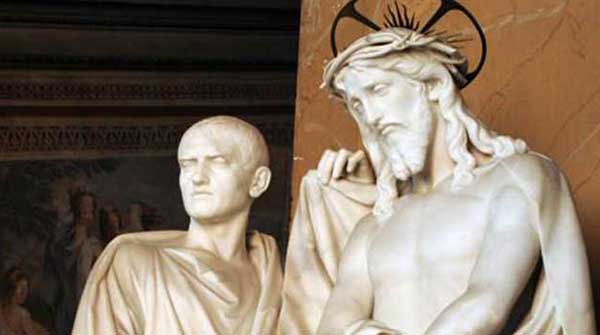

Pilate consciously misused his power to curry favour

As a Catholic schoolboy in 1950s Ireland, Easter was a mixed bag.

As a Catholic schoolboy in 1950s Ireland, Easter was a mixed bag.

Yes, we got a week and a half off school, which was never something to be sneezed at. And the days were visibly brightening, indicating the departure of winter.

But that was about it.

In contrast to Christmas, the lead-up to Easter was sombre. It had no joy or anticipation. If there was a prevailing mood, it could be characterized as gloomy. Ireland was a different place then. It took its Catholicism very seriously.

Starting with Ash Wednesday and the season of Lent, the process began roughly six weeks before Easter. Lent was a period during which we were supposed to practise self-denial as a form of penance. Adults talked about things like giving up smoking for the duration. Children would resolve to forego sweets. In my experience, most such resolutions fell by the wayside, albeit with varying degrees of associated guilt.

|

| Related Stories |

| Hippity hoppity: following the trail of the Easter bunny’s origins

|

| The overwhelming imagery of the Crucifixion

|

| Pope Francis more highly respected than the Catholic Church itself

|

Then came the days immediately preceding Easter Sunday. This was when the mood really kicked in.

The local cinema shut its doors, and proceedings in church were particularly solemn. Statues were shrouded and the grim crucifixion narrative dominated. There was a sense of foreboding in the air.

And one of the people we contemplated was Pontius Pilate.

Although details of his life are very sketchy, Pilate was a bona fide historical figure. We may not know much about him but we do know that he was real. And the evidence isn’t just from the New Testament and a few ancient historical references.

An archaeological dig in the summer of 1961 unearthed a block of carved limestone with an inscription mentioning Pilate as having been prefect of Judea during the reign of Emperor Tiberius. The artifact was found at the coastal site of the old city of Caesarea Maritima, which was once the capital of Roman Judea. Known as the Pilate stone, it’s now in Jerusalem’s Israel Museum.

Although there’s nothing remotely definitive about Pilates’ background, it’s reasonable to presume that it contained some distinction. Perhaps he came from a prominent family. Or maybe he had some military accomplishment. You didn’t get to be Roman governor of Judea for 10 years without something going for you.

There’s also speculation as to what kind of governor he was.

Some suggest he was a “hard man,” insensitive to local opinion and thus prone to creating unnecessary friction. Others paint the picture of a weak, pliable character who could be bullied into doing what he knew was wrong.

His role in the trial and execution of Jesus is advanced as an example of the latter. He was, after all, the guy who sentenced Jesus to death.

The version of the story we were taught is that Pilate knew Jesus was innocent but bowed to priestly insistence on condemnation. Hence the infamous washing of hands.

For some, this kind of got Pilate off the hook. Not completely, of course, but at least in part.

Yes, he passed a gruesome sentence on an innocent man. But he didn’t really want to do it. The major fault lay elsewhere. And that elsewhere wasn’t difficult to decipher.

Subsequently removed during Vatican II, the term “perfidious Jews” was still part of the Good Friday liturgy in my childhood. It wasn’t necessarily something people thought much about. Most probably didn’t think about it at all.

It was just an uncontroversial statement of fact. Historically, a reluctant Pilate had been pressured by Jewish priests, as a result of which he ordered the crucifixion of Jesus. That’s what people believed.

Still, if you think about it, there’s no exoneration here for Pilate. It actually magnifies his culpability.

Pilate was a man entrusted with substantial power, including the power of life and death. Enforcing what we’d now view as harsh laws is one thing; inevitably, laws reflect the values and perspectives of their place and time. But consciously misusing that power to curry favour is a gross abrogation of responsibility.

Imagine it in terms of a scenario from an old western movie.

The lynch mob descends on the jail, clamouring for the prisoner. And the sheriff protests that there’s no evidence of his guilt. So far, so good.

Then it goes off script.

The mob isn’t placated, so the sheriff backs down. But rather than merely handing over the prisoner, he has his deputies fetch the rope and carry out the lynching.

Not a good look at all!

Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well, perhaps a little bit.

For interview requests, click here.

The opinions expressed by our columnists and contributors are theirs alone and do not inherently or expressly reflect the views of our publication.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.