In late 1965, coming to Canada from Ireland had its revelations.

In late 1965, coming to Canada from Ireland had its revelations.

My Dublin hometown may have been more architecturally distinguished, but it couldn’t match Toronto’s relative abundance of decently paying jobs. There were also things like diners – which I’d only seen in American movies – and the language esoterica pertaining to “double-double” coffees.

Top 40 radio and the ubiquity of Christmas music were other discoveries. It wasn’t that we never heard Christmas tunes on Irish radio. Of course, we did. But we experienced nothing comparable to the volume populating Toronto airwaves.

CHUM – the younger demographics’ preferred station in Toronto – included several in its regular 1965 rotation, one of which was a paean to Honky the Christmas Goose. Rendered by the Maple Leafs’ musically-challenged goaltender, Johnny Bower, Honky’s tale was strictly a novelty item. But Elvis Presley’s Blue Christmas was a different animal.

Blue Christmas wasn’t a new song and Elvis wasn’t the first to do it. He was, however, the guy who transformed it from also-ran to seasonal classic.

Blue Christmas was the brainchild of an advertising jingle writer who lived in Connecticut and commuted to work in New York City. If you watched the Mad Men television series, think of him as one of those guys – a post-war suburban white man who earned his daily bread on Madison Avenue.

His name was Jay Johnson and creating images around words was his professional forte. Music, though, not so much. So advertising having taught him the value of collaboration, he enlisted a musician friend – Billy Hayes – to add that dimension.

Next up was finding a publisher, which resulted in the song being placed with a Roy Rogers wannabe called Doye O’Dell. The year was 1948, singing cowboys were popular – Gene Autry had scored big with Here Comes Santa Claus the previous year – and fingers were crossed. Alas, O’Dell didn’t deliver any commercial joy.

However, a feature of Christmas is that it comes around once a year. So if at first you don’t succeed, you can always try again. And they did.

There were three Blue Christmas placements in 1949. One was a lush orchestra/chorus treatment by Hugo Winterhalter, another was a conventional vocal from Russ Morgan and the third was a country version by Ernest Tubb.

The first pair enjoyed some success without setting the world on fire and Tubb had a significant hit in the country market. But country, disdained as hillbilly by some, was a relatively small slice of the commercial pie. A Christmas hit there wasn’t going to make you rich.

Still, the Tubb record was portentous in its own way. Elvis, a young working-class southern boy who loved country music, heard it and liked it.

Blue Christmas continued to attract some attention after 1949. The very popular Billy Eckstine took a crack at it in 1950. But his “nice, tasteful arrangement” didn’t do much in the marketplace.

So if you were a singer looking for seasonal material, Blue Christmas wasn’t shaping up auspiciously. You’d be inclined to look elsewhere.

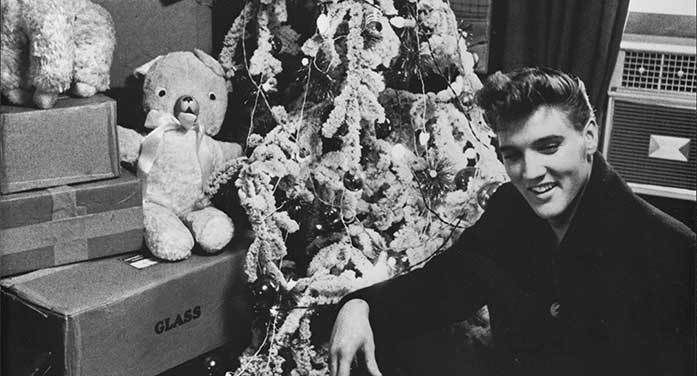

The Elvis version dates to 1957 and his first Christmas album, which itself was highly controversial. The idea of someone nicknamed Elvis the Pelvis tackling sacred carols like Silent Night and venerable secular favourites such as White Christmas gave some people conniptions. Or so it seemed.

The Elvis version dates to 1957 and his first Christmas album, which itself was highly controversial. The idea of someone nicknamed Elvis the Pelvis tackling sacred carols like Silent Night and venerable secular favourites such as White Christmas gave some people conniptions. Or so it seemed.

In retrospect, the whole fuss had a contrived sense to it. Entities like Time magazine could simulate faux derision while Elvis and his record company banked the proceeds. Meanwhile, people on all sides got to act out their predispositions.

Taking the Tubb version as its starting point and adding a keening soprano backing vocal, the Elvis recording infuses Blue Christmas with a bluesy sense that’s miles away from previous interpretations. And although initially overshadowed by the controversy around other songs on the album, since the mid-1960s it’s evolved to Christmas classic status.

It’s a master class in how something hitherto quite ordinary can be transformed by a specific performance.

Johnny Marks – the man who wrote Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer – said something similar to Autry about Autry’s recording of his song: “What I sent you in 1949 were ink dots on a piece of paper. You had to translate this into a sound, lyrically and musically, that people would like. How many great songs have been lost because of the wrong rendition?”

Troy Media columnist Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well, perhaps a little bit. For interview requests, click here.

The opinions expressed by our columnists and contributors are theirs alone and do not inherently or expressly reflect the views of our publication.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.