As the clock winds down on 2019, it’s time to ponder what the coming year may have in store for the Canadian economy.

As the clock winds down on 2019, it’s time to ponder what the coming year may have in store for the Canadian economy.

To provide some context, 2019 hasn’t been a great year for the economy, with inflation-adjusted gross domestic product (GDP) expanding by around 1.6 per cent. This was less than growth in both 2018 (two per cent) and 2017 (three per cent).

But job creation has been surprisingly robust given rather tepid economic growth. On an average annual basis, 2019 should see a solid 2.2 per cent jump in the number of jobs.

Looking at the composition of GDP growth, the data shows that consumer outlays, housing and government spending have been driving the bus. Business investment has been sluggish, while small gains in Canada’s exports have been offset by rising imports, meaning that little growth is coming from net trade.

The next two years will probably bring similarly feeble increases in GDP, in line with 2019’s uninspiring performance. Job creation is likely to decelerate amid tight labour markets (fewer jobless workers are available to fill vacant positions) and escalating labour costs.

An unexpected development in 2019 was the return to a period of falling interest rates. When the year began, most forecasters were expecting both the Bank of Canada’s policy rate and market-based interest rates to continue creeping higher, on the heels of earlier rate increases in 2018. But that didn’t happen. Instead, interest rates dropped over much of 2019 – not just in Canada but in the U.S., too.

As 2020 approaches, there’s little evidence that interest rates are poised to climb in the near future. That’s good news for the millions of Canadians shouldering record debts.

In its Dec. 4 update, the Bank of Canada signalled a steady-as-she goes stance. The central bank sees a somewhat fragile Canadian economy that faces risks due to evolving international trade conflicts, weak global growth and heavily-indebted domestic households.

However, economic activity in Canada is being underpinned by pockets of strength, notably a rebound in housing markets and surging immigration. At this point, the best bet is that interest rates for savers and borrowers will remain fairly close to current levels over the next 12 months.

As for business investment (which excludes housing), the picture is mixed. Escalating government-imposed costs, waning competitiveness, infrastructure bottlenecks and challenging commodity market conditions are significant headwinds for the natural resource-based industries that supply more than half of Canada’s merchandise exports – and almost 80 per cent of exports from the four Western provinces combined.

Other than the massive investment planned by LNG Canada in British Columbia, capital spending is likely to remain subdued across most segments of the natural resource economy.

The outlook is brighter in some other industries, including technology, tourism, scientific and technical services, business services, and the rapidly expanding digital sector. In aggregate, real business investment probably won’t make much headway in Canada in the next two years.

Housing is a complicated story. Many housing market indicators have revived in recent months, fuelled by lower mortgage rates and record levels of immigration. Going forward, the demand for housing should remain brisk in the major cities where most new immigrants settle, notably greater Toronto and metro Vancouver. Nationally, housing starts in 2020-21 are likely to closely track the 210,000 starts projected for 2019.

Finally, let’s look at international trade. In recent years, Canada has been losing ground in surveys of global competitiveness. At the same time, most of our export-oriented industries are losing market share in the foreign countries that Canada sells into.

When these sobering trends are added to a slowdown in the U.S. and a soggy global economy, it is difficult to summon up optimism about Canada’s export prospects, certainly in the near-term.

For 2020-21, net exports are unlikely to contribute much to economic growth. While real exports are expected to increase modestly, in part due to higher oil shipments, this will be largely offset by a rising volume of imports.

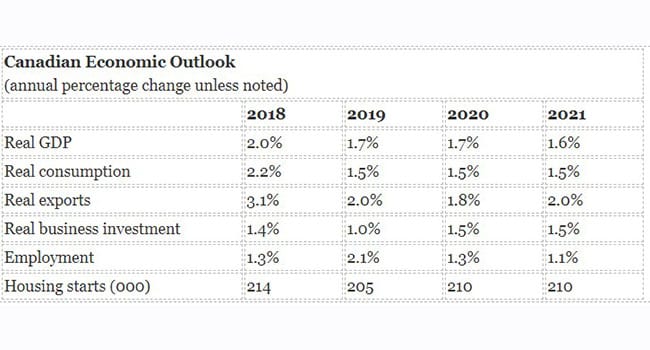

The table below summarizes my year-end outlook for the Canadian economy.

| Canadian Economic Outlook (annual percentage change unless noted) |

||||

| 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | |

| Real GDP | 2.0% | 1.7% | 1.7% | 1.6% |

| Real consumption | 2.2% | 1.5% | 1.5% | 1.5% |

| Real exports | 3.1% | 2.0% | 1.8% | 2.0% |

| Real business investment | 1.4% | 1.0% | 1.5% | 1.5% |

| Employment | 1.3% | 2.1% | 1.3% | 1.1% |

| Housing starts (000) | 214 | 205 | 210 | 210 |

Jock Finlayson is executive vice-president of the Business Council of British Columbia.

Jock is a Troy Media Thought Leader. Why aren’t you?

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.