While the government deserves applause, there are some gaps in the plan

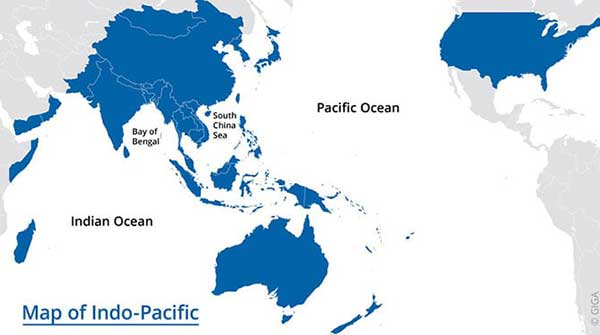

Several years in the making, Canada’s Indo-Pacific Strategy has finally been released. It’s a welcome fresh take on a time-worn tradition of trying to engage more substantially across the Pacific.

Several years in the making, Canada’s Indo-Pacific Strategy has finally been released. It’s a welcome fresh take on a time-worn tradition of trying to engage more substantially across the Pacific.

In one of many previous attempts, the Asia-Pacific Foundation was created in 1985 in Vancouver to foster dialogue. In another, a “Year of Asia-Pacific” was declared in 1997 while hosting APEC meetings. With those and numerous other initiatives mostly forgotten, the latest plan is a worthy recommitment to try again.

The primary reasons given are commercial. The region is Canada’s second-largest export market after the U.S., with $226 billion in annual two-way merchandise trade, accounting for 11 per cent of Canada’s total merchandise exports last year. Trade in services has grown by 80 per cent since 2010. The region includes six of Canada’s top 13 trading partners: India, Japan, China, South Korea, Taiwan, and Vietnam. Two-way investment flows in the past two years have totalled $64.4 billion.

|

| Related Stories |

| Canada’s Indo-Pacific Strategy: What’s the end-game with China?

|

| Canada and the Indo-Pacific: Slow boat to Cold War 2.0?

|

| Canada effectively absent in the Indo-Pacific |

Mirroring the U.S.’s Indo-Pacific Strategy announced last February, the Canadian version sets out five generic objectives: promoting peace, resilience and security; expanding trade, investment and supply chain resilience; investing in and connecting people; building a sustainable and green future, and acting as an active and engaged partner to the Indo-Pacific.

The list of new initiatives, released in a Backgrounder document, includes 27 projects costing $2.3 billion over five years. The biggest ticket items are $750 million to back a G7 initiative for infrastructure in the region, $493 million for the military, $133 million for two feminist assistance projects, and $100 million for new diplomatic positions.

Of course, even a good plan can be critiqued and there do appear to be some gaps.

First, there is no mention of the demographic time bomb facing the region, most notably in Japan, China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, South Korea and Singapore. Declining and rapidly aging populations will change trade and investment dynamics and shift governance priorities fundamentally over the coming years. China and Japan already face serious economic difficulties. How this is accounted for in our new strategy is unclear.

Second, viewing India as a pre-eminent partner belies decades of frustration in our bilateral relations. India is a large potential market, but it has been disagreeable on trade rules, especially in agriculture. As for common democratic values, India stays sharply focused on its interests. It notably abstained from the U.N. resolution condemning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Third, characterizing the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) as a unified entity with which to prioritize relations glosses over the fact that it is a loose association of very different countries. Yes, we should conclude a free trade agreement with ASEAN. But managing relations with Indonesia or Myanmar is profoundly different from doing so with Singapore, the Philippines, Brunei, etc.

Fourth, if China follows Russia’s example in Ukraine and attempts to take Taiwan, as it has repeatedly vowed to do, all current plans for the Indo-Pacific region would be turned upside down. Spending on defence assistance alone would skyrocket. While referencing the need to be “clear-eyed” about China, the strategy neither sets out nor references the need for a contingency plan to address this particular elephant in the room. It would, in short, yield severe consequences for Canada and the world.

Fifth, hiring more people may be a natural reflex, but we already have excellent ambassadors and trade commissioners distributed across 22 Asia-Pacific countries, including no fewer than 14 regional offices in China and eight in India, all backstopped by thousands of experts at Global Affairs Canada and other specialized departments in Ottawa. With our provinces also present in 33 offices in Asia-Pacific, along with innumerable trade associations and chambers of commerce, co-ordination would seem to be a bigger challenge than staff shortages.

Finally, many would agree that success in the region will be primarily driven by our own domestic actions. The expected 2025 completion of LNG port facilities at Kitimat, B.C., which will enable our first-ever gas exports to Asian markets, represents probably the single most important contribution we can make to the region, to the transition away from coal, and to our own economy. The multi-national diversity of the companies with stakes in the $40 billion+ LNG Canada project – Shell (UK) 40 per cent, Petronas (Malaysia) 25 per cent, PetroChina 15 per cent, Mitsubishi (Japan) 15 per cent, Korea Gas Corporation 5 per cent – tells us what the region and the world really need from Canada.

Answering that demand might just make Canada a real player in the Indo-Pacific region someday. In the meantime, the government deserves applause for making a fresh start.

Randolph Mank is a former three-time Canadian ambassador in Asia and VP Asia for BlackBerry. He currently heads MankGlobal consulting, serves on boards, and is a Fellow of the Canadian Global Affairs Institute and the Balsillie School of International Affairs.

For interview requests, click here.

The opinions expressed by our columnists and contributors are theirs alone and do not inherently or expressly reflect the views of our publication.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.